A Reflection on George Floyd’s Death and the State of the Nation

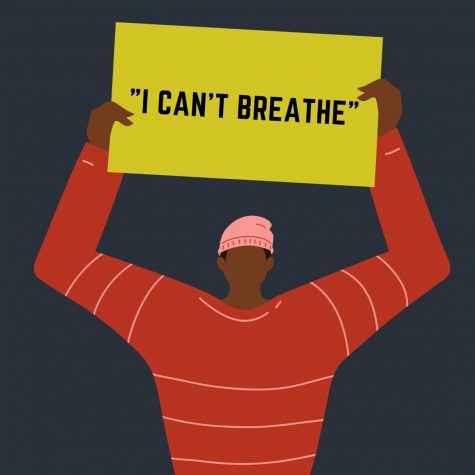

George Floyd’s death at the hands of Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer, has re-ignited the deep wounds of internal division along racial lines.

The ensuing reaction to the incident featured a combination of peaceful protests, destructive riots, and intense internal turmoil among people across the nation.

When we examine the reaction to the incident, it seems that there has been more media interest garnered towards the reaction to Floyd’s death than to the underlying reasons for those reactions.

I understand why, from a news organization perspective, the national spotlight is focused more on destructive riots and businesses being engulfed in flames than the routine injustices that caused them. It’s more newsworthy.

But it’s more difficult to understand the underlying causes of the frustration of the black community that gave rise to this response. Obviously the riots, looting, and destruction that has occurred is a misguided and immoral response to the tragedy. These actions are illogical and often counterproductive to the aims that the perpetrators wish to achieve. Yet the vast amount of protests that have occurred have been peaceful and non-violent.

Because I believe a discussion of the underlying roots of the crisis is more important in the grand scheme of American society, I’d like to shine more of a spotlight on the arguments of the protestors and activists, instead of discussing in-depth the incidents, riots, and looting that have started in reaction to Floyd’s murder.

I think what we are missing as a nation is the principle of human dignity and respect. The polarization of the issues of police brutality, and, in a broader sense, racial inequality, are all closely connected to the lack of respect and understanding that Americans have for each other.

The primary issue behind the vast majority of the racial injustice that occurs in America is the dehumanization of black and impoverished persons that persists because of a lack of understanding of their situations. Because this point is so important, I’m going to be detailed in explaining exactly where the disconnect is.

What Happened?

Though we’ve seen time and again people try to explain away these types of tragedies, now, more than ever, it seems obvious that there aren’t any easy answers. Floyd’s death was a senseless tragedy which no empathetic human being could defend. But the ensuing protests address a larger set of issues on which people disagree. One side favors maintaining the status quo, or at least does not believe in making significant political and social changes to radically reform criminal justice. The other finds the current system oppressive and wants systemic reform.

To be clear: George Floyd was killed by one person: Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin. No other person (except, perhaps, the other officers who watched the atrocity occur) can be held responsible for this action. Every individual is responsible for his or her own action; moral responsibility is the foundation for our entire justice system.

That being said, only a fool would argue that the choices that we make are completely free from the influence of the people, events, and social institutions in our lives.

What factors led Officer Chauvin to press his knee onto a subdued George Floyd for a period of no less than 8 minutes? Was it simply the case that this was just one ‘bad apple’ in a mostly good police force? Or does this event prove that the entirety of the police and criminal justice system is racist?

Neither answer is completely correct. Floyd’s death was not the first unjust death of a black man or woman at the hands of a police officer. The situations vary extensively, but Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Rodney King, and Malice Green are a few of the well-known names of police brutality victims. Even beyond the newsworthy cases, however, there exists a general lack of regard for human dignity, specifically black human dignity, among the institutions of justice in America.

The way that we improve is to help people understand what is going on. It can work, and I’ve seen it before. But for the sake of helping people understand, let’s address this argument more fully.

In line with the theme of empathy, let’s assume the position of the detractors of the protests, the activists, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Why Does the Status quo Need to change?

Some will argue that the premise of a ‘broken system’ is simply an excuse to cover-up the laziness and immorality of those individuals that “choose” not to succeed.

Such might be the musings of many Americans who do not sympathize with modern movements pushing for racial equality. Although they might not verbalize these thoughts, it is not at all a far cry from the public statements of many who oppose these movements.

A skeptical reader may now criticize me for using hypothetical arguments as ‘strawmen,’ especially if they believe that the problem is entirely in the mindset and lifestyle of black and inner-city folks for staying in the same system. To be clear, I use hypothetical arguments like the above because they don’t call out any one person and can be more broadly applicable to anyone. I think this prevents pointing fingers and aids the mission of unity and empathy towards both sides.

However, I also recognize that it may be necessary to identify this line of thinking for the logical integrity of my own argument. Please note that, in addressing this argument, I hope not to humiliate, shame, or degrade, but to explain.

Andrew McCarthy, a popular conservative writer at the National Review published an article on June 3 titled “The ‘Institutional Racism’ Canard.” In it, he states that it is a fallacy that black Americans are more likely to be targeted by police than white Americans.

McCarthy explains that, in reality, “the most dangerous threat to the African-American community in America is not cops. It is liberals. The United States is not institutionally racist.”

Part of his argument against ‘institutional racism’ is that, although blacks are disproportionately shot by police compared to whites, this is not an accurate representation of racism because factors other than race explain this discrepancy. African-Americans, though making up only about 13% of the population, commit “53 percent of murders and 60 percent of robberies,” he points out. McCarthy also notes that the number of unarmed black men killed by police represent just .1% of black homicide victims.

McCarthy eliminates in his calculation of wrongful police shooting those who were shot by the police and armed. The implication here is that since these people were armed with a weapon when killed by police, their deaths were justified or excusable.

Human life is valuable, no matter who the human is. And it isn’t as cut and dry as McCarthy’s article would suggest. A recent CNN article reported that “African-Americans are at greater risk of being killed by police, even though they are less likely to pose an objective threat to law enforcement, according to research by Northeastern University Professor Matt Miller. The research found Hispanics are also more likely to be victims of police shootings.”

The same article also notes that, according to research from Northeastern and Harvard University analyzing data from 2014-15, among those who were “unarmed and appeared to show no objective threat to police, nearly two-thirds of the victims were Hispanic or Black,” the researchers found.

More information needs to be uncovered for this statistic, however. An unfortunate reality of the lives of many in the inner-cities is that young men often feel required to possess a firearm at all times for self-defense. These firearms, often illegally bought or owned, are sometimes used for protection from rival gangs or other would-be shooters. When the threat of being killed by a neighbor is so high, as it often is in crime-ridden areas, some elect to carry weapons with them.

Obviously, this makes this person more likely to be shot and killed by police. Keep in mind that the people born into this situation are disproportionately black. In other neighborhoods, especially predominantly white ones, where crime is less common, there may be less of a threat of violence and thus less of the perceived need to carry a firearm.

Now, as you can see, as a result of the social system that they are being brought up in, African-Americans are more likely to be in a position where the police may use lethal force. Is it the fault of those who are brought up in this system or is it the fault of those who have designed the system? Is it both?

Part of the reason that many minorities, especially low-income blacks, fail to achieve financial and social success is that they start life out in a system where it is significantly more difficult to complete these goals than in middle-class America, or even abroad.

Consider that, according to a 2018 study, “African Americans are 2 times more likely to die as infants, 3.6 times more likely to experience childhood poverty.” If you have a heightened risk of death before you reach your second birthday, how can you be said to have an equal opportunity to succeed in any other aspect of life?

It’s a vicious cycle in which black youth have no hope because as soon as they are born, they are placed in an endless trap to keep them in low-income regions with violence, drugs, broken families, and crime.

Rapper and activist Meek Mill comments on this phenomenon in his outro for the song “Oodles o’ Noodles Babies:”

“See, I got homie that’s a billionaire

And I be tryin’ to explain it to him like,

If your mom ain’t on crack or if she got a job and she doing eight hours a day

And your daddy in the graveyard or in the jail cell,

who the f*** gon’ babysit?”

The Other Side

Empathy goes both ways. There are certainly points of merit on the other side of the ideological spectrum as well. McCarthy’s argument criticizes the concepts of “institutional racism” as a metaphorical paintbrush to paint any police malfeasance as racism.

I agree that the police do not go “looking for people to shoot.” I also agree that, in terms of pure numbers and scope, homicides within minority communities (or ‘black-on-black” murder) is a more significant issue than police killings of African-Americans.

Those on the ideological right on this issue present a valid point when they warn against categorizing all or most police as racist. I genuinely do not believe that most police, white people, or any other people in our society, are actually racist. A relatively small percentage of Americans do believe that certain races are better than others, or that segregation should exist. It is, of course, impossible to know the exact figures of racists in America since we can’t accurately judge what is in people’s hearts. However, we know that significant strides have been made in changing public opinion regarding race since the mid-20th century.

There are still cases where blatant racism occurs and someone insults or degrades someone purely on account of their race. But we must recognize that the more significant instances of racism manifest themselves in socio-economic traps, housing and bank loan discrimintion, mass incarceration, sentencing discrepancies, and police brutality. These areas, with the possible exception of police brutality in recent years, get considerably less media and public attention.

Related to this point is the fact that racism does not have the same effect on every black person. Some of the struggles discussed above are more closely tied to class as opposed to race. Of course, black people are disproportionately born into circumstances of poverty and low socio-economic status, but this is not an absolute association.

Plenty of black people and other minorities are born into the middle and upper-classes and do not face any of these challenges. I believe all black people are at least a little bit affected by the plight of other blacks; as Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

But racism isn’t the biggest problem for every black person in the country. Millions of black families live their everyday lives with focus on healthcare, employment, housing, and other concerns that are not directly related to race. And there are certainly plenty of white people who are in situations worse than certain black people.

No one should be saying that all persons of one race are more oppressed than all persons of another race. If you are middle-class, educated, healthy, black, you likely have a similar chance to succeed as someone with all the same qualities and is white. The problem is getting there.

So it isn’t really that all of America is racist, but that there exist significant barriers that prevent ethnic and racial minorities from achieving significant social and economic gains.

What’s Next?

As we remember the life of George Floyd and all the victims of police brutality and injustice, it is of the utmost importance that we remember that no matter what political side we find ourselves, we are all human. And every single one of us deserves to have their human dignity respected.

Faced with the reality that the threat of dehumanization is very real, and that racial injustice persists in our society, we must make changes. Just because there are points of merit on both sides of the race relations argument doesn’t mean that we should do nothing. Let’s discuss what changes need to be made in a civil and democratic manner, but they must be made. The status quo cannot continue.

It’s also important to note that the two sides of the argument are not “equal”. I’ve noted that there are certain valid concerns that people have with the various black activist movements across the country, but in large part I support their efforts and believe that they are closer to being on the right track than those who advocate doing nothing. But a significantly more nuanced approach will be crucial to achieving any real positive change.

In foreboding times like the present, it is easy to turn our backs on each other and further cement our positions and ideologies. But let us remember: if we listen to our peers and fellow citizens with an open-mind and heart, we will be able to unlock greater problem-solving potential and move closer to achieving peace and justice.

Ihsaan Fanusie is the sports editor for the Reporter, as well as a writer for the news and sports sections. He enjoys reading and writing and can be found...