At 7:55 a.m. on Oct. 7, a bus full of 40 Stetson students, led by Dr. Marvin Dunn, a Professor Emeritus at Florida International University, embarked on a bus tour of historic yet neglected African American history sites in Central and Northern Florida. Students signed up to attend this tour for a variety of reasons, but many expressed an interest in learning a history that is not taught in textbooks.

For Kaise Tinglin ’26, the trip was a time to play a part in continuing this history for others. “Just having the opportunity to come out here and learn about this truth, this history that is sadly being erased slowly by the local community and state and federal government as well. I wanted to be a part of ensuring that this history doesn’t get erased.”

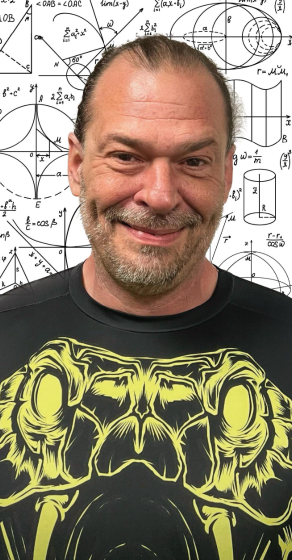

The overnight trip was free for Stetson students thanks to funding provided by the Miami Center For Racial Justice. Stetson Director of Community Engagement, Kevin Winchell, described the trip as “. . . an initiative for any students who care deeply about social and racial justice.” And went on to comment, “it wasn’t hard to fill a bus with people who cared about this cause.”

Winchell, a friendly face who eagerly accompanied students on the trip, noted Stetson University’s responsibility as a private institution in the state of Florida to participate in these discussions. “Public institutions have recently had many prohibitions placed upon them about what they’re able to teach, what they’re able to discuss. And private institutions don’t have the same sorts of restrictions. That means that we have a responsibility to use our privilege of being a private institution to fill that gap . . . that our public institutions can’t touch.”

For Dr. Marvin Dunn, the cause is much greater than institutional values. When asked why he believes it is important to have these tours, he answered “Students are young, and they will pass these stories on to their children and to their grandchildren. And I think students can have hopes that some students in particular have a hunger for knowledge and want to know what happened.” This is a sentiment that would be repeated many times throughout the trip.

A somber tone was set on the first day when the group gathered around the Hallowed Ground of the Ocoee Massacre, a burial ground nestled in an unassuming residential neighborhood.

“I think looking at the Ocoee site, that is a burial site for, I don’t know, but upwards of 300 people buried there in a mass burial. And the starkness of it, the simplicity. It’s just grass. It’s just a field. It’s just a fence that someone put up,” said Dr. Paul Croce, a Stetson Sr. Professor of American Studies who urged his students to attend and even tagged along himself. He paused thoughtfully, then added, “. . . it shows a disparity between the fencing awareness and the lack of attention to the severity of the crime that happened there.”

Students asked questions about the surrounding neighborhood and the residents’ perception of the site, eliciting a discussion of the tendency to shy away from the uncomfortable realities of American history. A point that Stetson Political Science major, Selah Williams ’24 emphasized, “I think we’re in an age right now, especially in Florida, where it’s being erased, but specifically the hard truths of American history, which focus on African Americans.”

The group spent the rest of the day in Live Oak to learn the truth about Willie James Howard, a 15 year-old lynching victim who was targeted due to a letter that he wrote and sent to a white girl. His story was included on the tour route in an effort to correct the inaccuracies in how his death is remembered. This section of the tour was accompanied by Douglas Udell, a Live Oak local and friend of Dr. Dunn, who followed the group for a few stops to tell Willie James Howard’s story.

Students were uniquely impacted because the bus route loosely followed the path from the Five and Dime store Willie James worked at in downtown Live Oak to the Suwannee River bank where he was lynched. Ending with a solemn visit to the gravesite that Udell had erected for him in 1994, the group held a moment of silence and prayer for Willie James. During this time, students had the opportunity to reflect on his life and memory. “But I know that in his moment, he was brave, and he was courageous. And he did a lot in his fifteen years than a lot of people do in their lifetime. So I just tried to keep that positive mind and acknowledge his life,” said Selah Williams ’24.

For Douglas Udell, the Suwannee River will never evoke the joy that it is famously known for. “I’ve gotten used to it. I grew up on the river. And I knew about the river so I never fooled with the river . . I don’t swim in that water. I won’t fish in there. I won’t eat fish out of it.” He struggles emotionally to tell the tragic story of Willie James Howard even as kayakers pass by none the wiser. But Udell accompanies the Teach the Truth tour because he sees the importance in spreading the hard truths of beloved Florida sites to younger generations amidst recent political interference with education standards.

“Because the history of how life was in America, for people of my persuasion is being lost. Our governor, this state, don’t even want you to learn it. They holler ‘woke, get rid of woke.’” Udell paused to look over the students walking with him before turning back to the mic and adding, “Woke don’t mean nothing more to me than being aware. Are you asking me not to be aware? I want you guys to be aware of everything.”

The second day of the trip took the group to Rosewood, Florida, the site of the 1923 Rosewood Massacre. During the seven-day massacre, a white mob from the neighboring town of Sumner destroyed Rosewood and murdered several Black residents due to a falsified claim that a Black man had assaulted a white woman in Sumner. Presently, there are six confirmed African American victims and two white victims of the Rosewood Massacre; however, some estimates range from 27 to 150 African American deaths. Rosewood’s historical memory is shrouded by misinformation and resistance from the current community to recognize its significance.

At the time of writing, Dr. Marvin Dunn is the only African American to own property in Rosewood, which he intends to turn into a federal historic site to use as an educational center. As participants of the fourth Teach the Truth tour, Stetson students were allowed to visit the property in one of its earliest stages of development; the land consisted of a partially wooded area with a tent, two piles of brush, and a path that used to be the guiding railroad tracks for many Rosewood residents who fled to safety during the massacre.

Together, the group walked the now barren railway path and listened to Dr. Dunn’s story of Rosewood. After an engaging discussion of the backlash Dr. Dunn has experienced in his efforts to preserve the property, students were asked to help the site’s caretakers clear the remaining brush into two large bonfires. What seemed to be a begrudging task turned out to be just as moving as previous parts of the tour. Stetson students worked as a team to carry branches and logs to the fires and expressed interest in playing such a hands-on role in preserving historic land. Jayda Precil ’25 looks forward to the future of the property: “I think it’s very important, because I think, you know, obviously, we’re playing a part in like . . . very important history, if it becomes a national park. And even then, we’re still playing a part, whether it does become a park or not . . . So I feel like it just made a big impact.”

The tour ended at the J.W. Wright house, where African American women and children were hidden from the mob on the second floor by its white owners. The Wright home is the last building still standing in Rosewood from the time of the massacre, and Dr. Dunn hopes that it, too, will be preserved. In the last official group discussion of the tour, Dr. Dunn emphasized the importance of students carrying on the information they learned to their friends, families and classmates. Though this was the last official group meeting, the discussion did not end at the Wright home; students spent the three hour bus ride back to DeLand comparing perspectives and grappling with difficult new information.

When asked what he would say to students who were not able to attend this Teach the Truth tour, Dr. Dunn was quick to answer, “The best way to learn history is to experience it directly, to go to the places where the blood was shed, where the heroes were made. And then you carry that experience in your heart. Because history is more than just facts. If all you write in history are just the facts of what happened. That’s not history. That’s a catalog. History is meant to be felt, and has to be felt, if change is going to occur as a result of bad history.”