“I stood in the African wing of the British Museum, eager to read a text panel on the origin of the dazzling art before me, but it explained, in detail, that the items on display were ransacked in retaliation—a member of that village had assaulted a British officer, and in turn, they destroyed the village. Soldiers were instructed to take as much as possible to ‘cover the debt of the retaliation.’”

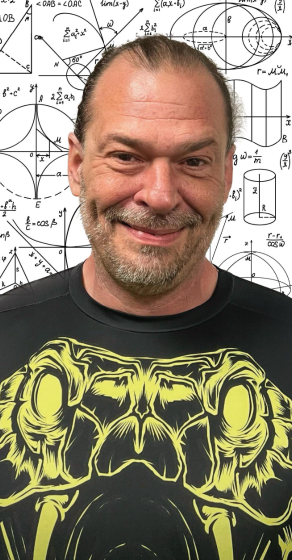

Placards like the one described by Director of Stetson’s Hand Art Center, Natalia da Silva, have begun to pop up in exhibits all throughout the British Museum over the course of the last few years. Refusing restitution—the return of items to their proper owners—is no new issue with British-based organizations. But following the recent robberies of several storeroom items, many supporters of the British Museum find themselves questioning how the establishment can complain of theft when that is essentially how the museum acquired the bulk of its items in the first place.

“The legacy of European-led theft or unethical acquisition of artifacts is lengthy and very contentious,” Natalia explains, “examples range from outright pillaging to cases where the individuals involved in an otherwise legitimate sale or trade did not represent any or all stakeholders.” Founded by the 1753 Act of Parliament, the British Museum was established by the purchase of the collections of Sir Hans Sloane, physician and later president of the Royal Society.

In his lifetime, Sloane had amassed almost 80,000 rarities, ranging from books and manuscripts to precious coins and medals. He specifically outlined in his will that he would only give his collections to the nation on the conditions that his heirs were financially compensated and that Parliament establishes a freely accessible museum for all to view his pieces—thus, the British Museum was born. However, Sloane’s collections were obtained unethically, reminiscent of the issues still plaguing the museum today. As a physician, Sloane worked as a doctor on a string of slave plantations in the then English colony, Jamaica. He used both Englishmen and enslaved individuals to first begin collecting plant species, and after wedding a sugar plantation heiress, used the proceeding profits to continue funding his acquisitions. Though his posthumous donation may have seemed a charitable act, the majority of Sloane’s, and consequently, the British Museum’s artifacts were acquired and purchased with the backing of slave exploitation and imperialist networks.

And the strange thing is, all the information on the founding of the museum is readily available all over their website, even with the acknowledgement that “Some ways in which objects entered the British Museum are no longer current or acceptable.” Natalia comments, “I found it curious that this information wasn’t even hidden. It was out in the open like it was normal to have and display these artifacts.”

Associate Professor of Art History and Curator of the Vera Bluemner Kouba Collection at the Hand Art Center, Katya Kudryavtseva, explains how the issues with the British Museum go far beyond restitution, however. “Basically, it’s threefold,” she notes, outlining that the major controversies we should be concerned with are the calls for restitution, the current police inquiry and the actual state of the building. “There are ongoing issues with the exhibition halls, where some of the collections are displayed. One of them was actually, you know, the collection of Parthenon Marbles. I mean, you have roof flakes, you have tile damage” says Katya, exasperated. This aging infrastructure and the plans to renovate have been an ongoing issue that predates even the COVID-19 closings. In 2018, there were reports of leakage in the Parthenon gallery, sparking concern surrounding the condition and keeping of these thousand-year-old marbles. “There were plans to update the building, because of course, it’s a historic building so it’s not like it was new,” continues Katya. “But right now they’re on hold, I guess until they figure out the theft situation, not only of course because the curator was fired, but also the director is gone, the deputies gone,” she adds.

Perhaps the catalyst for the dredging up of the British Museum’s string of scandals, the ‘theft situation’ refers to the reported 2,000 items missing from the museum’s records. In the past year, the British Museum fired one of its workers accused of stealing several artifacts, but Katya muses that “It’s interesting, because actually, it was reported to the museum a long time ago.” Several years prior to 2023, the museum was notified that one of its curators was selling its items online, but The British Museum dismissed the claims. “The museum denied any wrongdoing in items missing from the collection, and as a result, we have like 2,000 items missing,” she exclaims. The scandal has only caused more eyes on the museum, resulting in the resignation of the establishment’s director as well as the exposure of the museum’s flawed security and record-keeping systems. Even its digital archives only account for a little over half of the museum’s actual collections. “Now that the museum is in turmoil, the inventory will be done in multiple collections; but inventory is a time consuming project, which of course, will delay the development of the museum,” concludes Katya.

Despite the disorder sparked by delayed development and dismissals, the British Museum’s longest standing controversy, restitution, continues to be the underlying throughline. “There are a lot of countries that are demanding return for their cultural artifacts; the most celebrated cases are the Parthenon Marbles, Benin Bronzes but also the Egyptian Government wants Rosetta Stone” shares Katya. “You see museums in Germany returning stuff, you see actually other British museums returning stuff, you see American museums returning stuff,” continues Katya, “and the British Museum, which is basically saying, ‘We are here to preserve the collection, you know, to care for it.’ Then 2,000 items are missing from your collection and your claim of preserving stuff sounds a little bit shifty.”

Though the issues concerning the British Museum may indicate otherwise, the ethics of curation and ownership are not usually as contested. Natalia breaks down the negotiation process in relation to Stetson’s on-campus art museum, outlining the ideal proceedings between museum and artist. “It honestly rests on whether an artist is selling their own work. In this scenario, they produce a Bill of Sale, a Certificate of Authenticity, and ideally, define copyright and other contingencies,” she explains. “In cases where the artist is not alive or being represented by a different party, a lot of research is involved to make sure everything happens ethically.” And museums, like the Hand Art Center, are committed to going beyond just the ethical acquisition of pieces, but also ethical preservation. “We commit to caring for the object so that it is preserved for future generations, ensuring public access via exhibitions, appointments or digitization. And we do our best to prevent unethical deaccession,” comments Natalia.

Deaccession, or the official removal of items from museums for selling purposes, can be done for ethical reasons like inability to secure items or changes in the museum’s mission; but facilities like the British Museum with its crumbling infrastructure, security threats and repatriation refusals trends towards the unethical. Take the highly contested Benin Bronzes, still largely housed by the British Museum, even in the face of Nigeria’s continual calls to have them returned. “The Benin Palace was sacked, looted, destroyed,” starts Katya, “but the Benin Palace was not just the storage of artifacts; it was a major art patron. So when you destroy that, you also destroy institutional structures that have truly supported artisans in that area,” she shares pointedly. Of the nearly 5,000 artifacts referred to as the Benin Bronzes, all of which were forcibly taken during the Benin Massacre, only about 30 have been returned to Nigeria.

“I was disillusioned with Europe,” remarks Natalia, who had spent her formative years as an art history student in the museums of her home, referring to both Latin America and the Caribbean. “All anyone ever talked about was going to Europe. It was viewed as a rite of passage,” she adds. But when she finally got to experience the numerous exhibits lining the annexes of the British Museum, she was confronted with the sore reminder that so few of the items in their possession were obtained ethically. The museum itself, as a public institution, adheres to the 1963 British Museum Art that prohibits the return of any artifact unless “it is a duplicate, physically damaged or unfit to be retained in the collection.”

So, what can be done?

Well, in cases such as the Parthenon Marbles, the Acropolis Museum in Greece has been pushing for the reunification of the marbles for decades. Since the 2009 opening, Athens has had a place and exhibit for the marbles still in the British Museum’s possession, except Greece’s facility has proper ventilation and no leaky roofs—not to mention, the thirty six other marbles and the actual origin where they were found. As for Benin, they of course want their artifacts housed in their country of origin, but there are more steps to be taken than simply the return of items. “They’re interested in restitution, but mostly actually, they’re interested in programs of cultural exchange, of supporting contemporary artists,” shares Katya.

“To just return does very little for them,” continues Katya. The ‘them’ here refers to the dozens of countries that were and still are victims of the colonialist powerhouse that was the British Empire. “As much as we can condone encyclopedic museums for how collections are well done, there is some truth in the fact that actually it’s very bad that art produced by certain cultures is all there.” The British Museum prides itself on the knowledge that it is home to a diverse span of cultures, but apart from the wrongful ways in which they attained their artifacts, housing all these stolen items in one place is perhaps more a hindrance than a cultural help. Kayta adds to this point on art. “It should be circulating internationally,” she continues, “and this is actually very bad for the market value, the brand value of those artifacts.” Restitution refusal takes cultural art and artifacts out of circulation, and as a result, takes away income opportunities that would arise from the travel and exhibition of their country’s rightful pieces. “We can think we give something back and our job is done, right? Well, not with countries that do have colonial past,” Kayta points out. “They need development of institutions, and that can only be done through cultural exchanges.”

It is essential to not only return the items, but also ensure that there are facilities to house those artifacts. “When you return something, sometimes shipping is free and sometimes it’s not. I don’t think it should be free shipping,” jokes Katya. “There should be expenses associated with the development of infrastructure, in institutional support, and so forth.” Museums small and large, evident through feedback from Stetson’s very own Hand Art Center, are able to conduct business and respect artists in all the ways the British Museum seems to not be able to. So, this is the time to ask why that is; why does one of the world’s most revered museums continuously fail, especially when there are ways to fix it? And can we, as art patrons, sit idly by and watch it crumble?