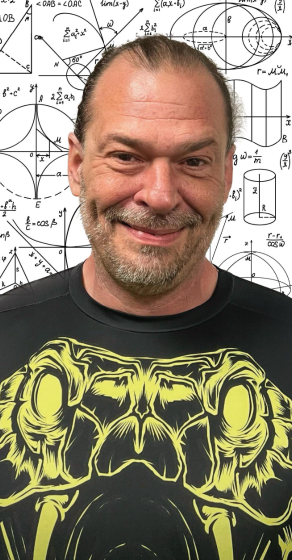

Whether through books, movies or video games, we find ourselves through characters and storylines. We learn ideas of good and evil from tales of heroes and villains and morals such as “slow and steady wins the race.” The impact of these values communicated through media is a small part of what Dr. William Chavez, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies, hopes to cover in his upcoming JSEM, “Religion and Video Games” in Fall 2024. Chavez, a relatively new professor to Stetson, was excited to tackle the requirements of Stetson’s JSEM, a writing enhanced course for juniors meant to develop students’ sense of personal and social responsibility.

One of the areas that Stetson considers to fall under the umbrella of personal and social responsibility is “Ethical or Spiritual Inquiry.” Chavez hopes to use video games to expand students’ understanding of religious practices and their function. Although the two appear seemingly unrelated, the connection Chavez draws between the two became clear to me as I sat down with him for an in-depth interview on the inspiration and intention behind his upcoming JSEM.

Chavez has a broad view of religion that includes the study of mythology. To completely submerge oneself in this mindset, he requests that students suspend the idea of belief as a necessary precursor for practicing religion – a large ask for college juniors juggling other classes. Early in the interview, Chavez discloses that his introduction to the study of religion was his undergraduate senior honors thesis on Satan and exorcism. He recalls a moment when a young relative asked him about his studies. At this time, he knew she was reading the Goblet of Fire, which he knew featured Mad-Eye Moody, the dark wizard catcher. Chavez tells her that he studies the equivalent of Mad-Eye Moody in our world. He says, “They call themselves and they remove demons from people. They also confront satanic worshippers, and who they think are things that go bump in the night. That’s who I studied.” He takes a moment to laugh before continuing to explain how his studies have morphed his understanding of what constitutes belief. In short, he feels that belief isn’t needed.

Chavez playfully challenges structure and established systems of thought. In his “History of Satan” course, for instance, Chavez explains that, “Even if the Devil and the Christian cosmos exist, our understanding of them is filtered through human ingenuity and human culture.” He questions not only the functionality of religion but takes a deeper look at how religion has socially impacted us in all of its forms. He says, “Disney and its early films are really fascinating. A lot of them are pulled from Brothers Grimm stories and European folklore. Princess dresses, medieval castle and cathedrals, none of those things are specific to American folklore and American culture. America has never had a kingship; The overwhelming culture is sort of airlifted out of European fantasy.”

You may not believe in gods associated with these myths, but are these tales of princesses in Disney or Nintendo games teaching you something about a cultural religious practice? What, or whose, beliefs are you practicing? The answer may surprise you if you have the pleasure of hearing Chavez dissect the Harry Potter series, where he feels that Voldemort’s storyline reveals something about our modern understanding of benevolence and punishment.With this in mind, Chavez makes a point that we may be subconsciously adjusting our ethics and beliefs in response to a larger and more rampant culture. More intriguing to Chavez is how those ethics and beliefs give gamers agency in how they experience the medium. Perhaps this is the opportunity to use video games to showcase how exercising agency in religion, either by choosing to abide by the predetermined “rules of the game” (what constitutes sin and what doesn’t) or forgo them, impacts individual religious experience.

For example, one game that Chavez finds intriguing when discussing agency in gaming is Friday the 13th: The Game. The objective of the game is for the camp counselors to survive the rampage of machete-wielding maniac Jason Voorhees. However, players will sometimes choose to ignore the rules of the game, and instead attack other counselors while Jason is on the loose. For example, taking a four-seater car and driving off in it alone–limiting other players’ odds at survival. Chavez reflects on these choices during gameplay saying, “They do it because they think it’s funny, or they do it because it’s vindictive. Having that type of realm of possibilities is something I want to engage with students of, “How are they acting? And how are they treating others in online spaces?” These possibilities gamers find in front of them by stepping into the shoes of someone else is one of the central questions of the class.

Fictional characters can remind us we aren’t alone in our experiences, and allow us to experience personal situations from a different perspective. During the interview, Chavez recognizes that gamers are more likely to play a game if they can experience it from a perspective of power. He argues that users are often attracted to video games because of the otherworldly capabilities they may come with. Chavez believes that there “is a power fantasy being exercised on what type of things can be done in games. That you can fly, that you’re really strong, that you can teleport, that you can do all of these moves and all these combos.” This sense of power can be relieving for the gamer as it allows them to reimagine frustrating scenarios with solutions or actions that can be cathartic. However, this same power has the potential for misuse.

If gamers decide to treat the digital space as a medium for their escapist fantasies, i.e. a way to “blow off steam,” it may impact the way they view their actions and the consequences of them. Chavez sets the foundation for discussing this by citing the “Benign Violation of comedy” theory from Peter Mcgraw and Caleb Warren, published in 2010. Chavez self-describes his understanding of the theory as such: “In the constructed simulated world of the joke, because it’s not real, maybe then you’re able to laugh at it. Because no one’s actually getting hurt, right? So even if it is a violation, even if the line has been crossed, it’s a benign one. It’s one that’s not actually substantiated or meant to have an impact.” In this simulated reality, their conversation may be limited to chat rooms or isolated voices from the heavens redirected through headsets. However, when the benign violation occurs, how separated are their simulated actions from their real impact? Chavez poses this question by asking, “Does cyberbullying exist online? If you are a trolling cretin in cyberspace, does that actually make you a trolling cretin in real life?” One aspect of reality that he admits has permeated gameplay is gun worship, and its real-life implications have long since been debated.

Amused, after recalling the existence of Wii Motion guns, a 3D printed plastic pistol where the Wii game controller can be inserted. Chavez shares that he is, “Utterly fascinated that gun worship is to that extent. That’s the best place for it to show up as a benign violation. They’re shooting bad guys…with their fake guns. But they’re also going…to make their gun, their fictional virtual gun experience, as realistic as it can be…” Chavez does connect traditional ideas of masculinity to hero worship, gun wars and weapon worship in mythology. He asserts, “Greek mythology is overwhelmingly defined by quest and combat. [Winning combat or a quest is how] you demonstrate that someone is worthy of praise or that they have some sort of social currency of which to praise.” While all of these are ideas he hopes to dive into in his upcoming JSEM this fall, he does not want students to think that he is searching for just one answer.

One thing that becomes clear throughout talking with Chavez is that he does not consider himself to be an activist. He has a reflective moment asking out loud to himself, “Do I study something to change it?” He pauses momentarily before continuing on, “I’m personally on the side of things where I don’t. I don’t really want to be influencing something. And I don’t really want to study something in order for me to change it.” In fact, he teaches religion to study it as an activity, practice and art that saturates us culturally and engages us. The awareness of the “why” is the reason he is ambitious enough to use video games, Disney, horror and the like to enhance students’ understanding of religion– to convince them they should engage with religion differently, independent of their personal religious beliefs and opinions. His upcoming JSEM promises to be the perfect place to play out the power fantasy of both religion and games.