The Fall 2020 Housing Dilemma

Top Left: Photo courtesy of Stetson Residential Living and Learning Instagram; Bottom Right: Photo courtesy of Marriott

The current pandemic has put universities all over the country in a precarious position as they attempt to open their doors to students in the safest way possible, and students have been left to deal with the repercussions.

On July 16, students were notified of fall housing changes and were asked to resubmit their housing applications if they wanted to live on campus. Stetson’s rationale for moving to single-occupancy bedrooms in the announcement sent out to students was that, “Unfortunately with a spike in COVID cases in Florida and many other states, we feel the need to adjust our plans. Based on a number of factors, including assessing health risks, examining local hospital bed availability, and listening to you, we have made the decision to increase the agency students have over their curriculum. We know that students will be spending larger amounts of time in their rooms as they use that space as their primary study location due to limited face to face activities on campus, at least for the start of the term. This level of occupancy also gives students needed privacy to fully participate in classes which may be online or hybrid.”

Priority for on-campus housing was given to international students, freshmen, and students who live more than 45 miles away and have under 90 credit hours.

By July 31, less than two weeks before the first day of classes, students were informed as to whether they had been given a housing assignment or not. For the many students who were not prioritized in the long list of students requesting housing, local hotels became the university’s solution.

Stetson arranged for rooms at four local hotels and offered this option to students at a price of $4,195 a semester, which is about $400 more than the cost of a shared dorm room and community style bathroom, and is the same cost of living in a suite style dorm. The price for living in the hotels for this length of time is usually more expensive, but Stetson is paying the difference to keep the cost lower for students.

Stetson promised that for those living on campus, the cost of housing would remain the same as what they originally planned on paying when they applied during the spring semester, regardless of where they were placed. Students relegated to hotels were not given the same luxury.

Hatter Network conducted a series of polls asking students about their opinions on the new housing changes on the Hatter Network Instagram account (@hatternetwork). Out of 162 respondents, 64 percent said they applied for housing. For respondents who applied, 46 percent were not offered housing, and therefore 24 percent opted to accept a room in a hotel. 35 percent will be living off campus, and 32 percent are choosing to stay at home for the semester.

Hatter Network also asked students for their own personal thoughts on the situation through Instagram. Jaxon Justiss (‘24), a music education major, responded, “I’m on a waitlist for a dorm or hotel, but I live 60 miles away and have eight classes starting at 8:30 a.m. and ending at 8 p.m. at the latest, and no money to pay for off campus [housing].” The closest hotel is less than one mile away from campus and the farthest is over three miles from campus.

Many students were offered a room in a hotel two miles away from campus, but were initially informed that students would be responsible for any transportation to and from campus. We called Residential Living and Learning to ask questions and express concerns over the situation; we were told that the form students filled out to pick if they wanted to remain on the waitlist for a hotel or dorm room had problems, resulting in multiple students being placed in the farthest hotel from campus after dictating that they didn’t have transportation.

For students who had expected to live on campus, finding out only a few weeks before the start of the semester that space might not be available can be frustrating. Emma Hall (‘21) said, “I feel that Stetson could have made its decision to kick people off sooner.”

Because many students weren’t offered housing by Stetson, they had no other options but to find somewhere to live off campus. Then, students ran into another problem: it wasn’t clear if students would retain scholarships or grants that require on-campus residence.

Mackenzie Shaw (‘22) commented on this saying, “I cancelled my housing application because my situation changed. Now I’m very worried because I had no idea my scholarships would get taken away! They should’ve let us know the consequences of not living on campus.”

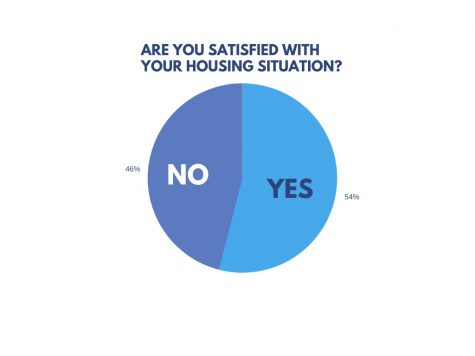

Of those who responded to Hatter Network’s poll on Instagram, 46 percent said they were not satisfied with their housing situation. Stetson has said that if COVID-19 cases continue to decrease and the situation permits in the fall or the spring semester, dorms will return to shared-occupancy and more students will be able to live on-campus. However, in such unpredictable times, the university can’t promise when more students will be able to return to campus and how the process will work.

As students begin to return to Stetson for classes in the midst of a global pandemic, campus life is sure to be entirely different. Unfortunately, despite constantly hearing the words, “we’re all in this together” in current news and media, many returning students feel left behind as the university makes changes to adapt to an unforeseen dilemma.

Emily Derrenbacker is an Arts & Culture writer for the Reporter and is in her second year at Stetson. She is double majoring in English and social...

Maxwell Smith is an opinion writer for the Reporter as well as the host of Maxxpolicy on WHAT Radio. He enjoys politics, coffee, the city of Chicago, and...