Two Cheers For Steve Levitsky

April 25, 2019

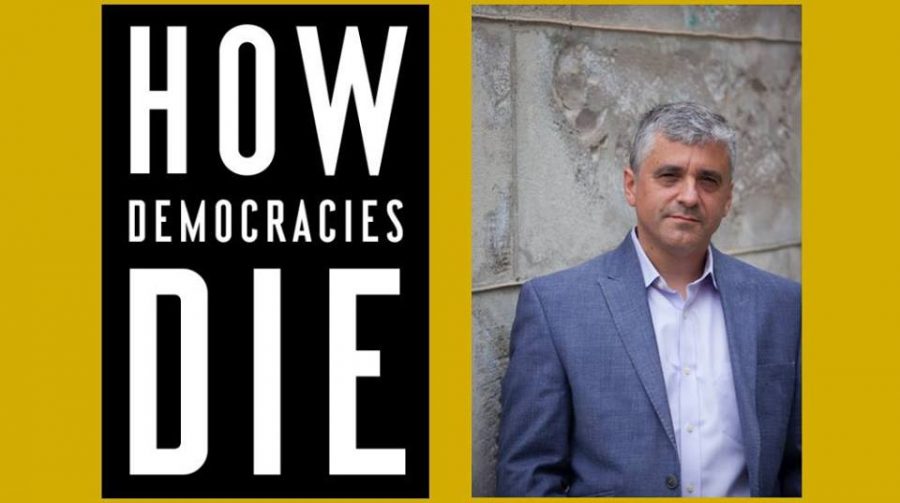

On Tuesday, February 19, students, professors, and community citizens filled the better part of the Stetson Room to hear Steven Levitsky. He is Professor of Government at Harvard University and coauthor with department colleague Daniel Ziblatt of the best seller, How Democracies Die (2018). Levitsky’s presentation lived up the dramatic intensity of his book. He provided a keen analysis of our present political weirdness: in the words of Stephen Stills, “somethin’ happenin’ here; what it is ain’t exactly clear” (Buffalo Springfield, “For What It’s Worth,” 1967, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gp5JCrSXkJY). Levitsky provided a lot of clarity.

Levitsky is worried about the erosion of democracy. Having studied democracies around the world, in health and in decline, he sees erosion in American “democratic norms” (100). The central agent of democratic decline, he suggests, is the sharpening polarization of political views.

Levitsky is no alarmist. He is not saying that the nation is heading to tyranny right now. And that’s because we have lots of democratic “guardrails” (97) including the checks and balances in the Constitution and a tradition of restraint in implementing power. After elections, there is no rounding up or exiling of the losers; they call the winners and turn to the job of loyal opposition—and they gear up for the next election.

But Levitsky is still worried, because despite that democratic history, the recent polarization has grown so intense that each side thinks the other has ideas that are downright dangerous for the country. Party polarization has in some ways even surpassed racial animosity; the number of Americans disapproving of marriage across party lines is now more than triple those who disapprove of interracial marriage.

With those partisan fears, citizens are more likely to jump the guardrails in favor of securing the nation from what they are calling the disasters that the other party will bring. Levitsky is not shy about identifying Trump as the chief agent of the more aggressive style of politics to address these fears. But the professor sees the president as a symptom of structural changes. Trump is speaking out about the fears that a lot of Americans are feeling; as Levitsky pointed out, “white male Christians used to be the faces of both parties and all elites; now they feel their country is being taken away” (February 19, 2019 presentation). He is not saying Trump is a demagogue, angrily expressing his supporters’ fears while shutting down debate and veering toward more unchecked power; but he is saying that the president has those tendencies. That is Levitsky’s current fear for our democracy.

The Harvard political scientist taps some history for examples of how Americans have avoided these dangers for democracy in our past. Levitsky regards political parties as major democratic gatekeepers. For example, before the present primary system for choice of presidential candidates, party leaders chose candidates in what he calls “invisible primaries” (57). Reforms in the 1970s gave average citizens more voice than those party leaders in their proverbial “smoke-filled rooms,” but that has also “made it easier for celebrities to achieve public support” (56) in defiance of establishment bigwigs. Levitsky praises the party leaders as gatekeepers of democratic values despite the democratic reforms that overturned the influence of those leaders.

Another example, when polarization was even worse than in our time: in the 1860s, the US went from polarized culture war over slavery and states’ rights to a shooting war. Levitsky explains how the nation healed from its wartime wounds. The region-centered parties of Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans found peace with each other after the Civil War, but at the expense of systematic racial segregation with almost all African Americans barred from voting, as Republicans largely turned a blind eye to these injustices.

While Levitsky provides astute analysis about dangers to democracy and reasons to worry about the potential for demagogues to rise from within our democratic system, these examples provide clues that there are downsides to the safeguards he proposes. Trust in party leaders? For all of their ability to gatekeep against extremists, they can also muffle the voice of the people. And sometimes calling out injustices gets people riled up enough to become polarized. When social problems run deep, how much can we trust our political leaders, who might just label calls for justice mere agitation. Did the (white) political party leaders after the Civil War overcome polarization? Sure ‘nuf! And they also postponed movements for Civil Rights by a century or more.

In our time, Levitsky sees erosions of democracy through the workings of a president who seems willing to play fast and loose with democratic norms. For example, Trump openly mocks establishment leaders of both parties; he calls criticism of his policies “fake news”; and he has supported attempts to “make it harder for minority citizens to vote” (183). These are dangers we need to notice and call out. But there are still more real dangers that Trump, along with liberal populists such as Bernie Sanders, are themselves pointing out.

Concentrations of wealth and of power have been on the increase in the last few decades. Conservatives tend to worry about concentrations of public power, especially with government regulations, and liberals tend to worry about concentrations of private wealth, especially in corporations. Both agendas leave the average citizen squeezed. And despite the worries of the current occupant of the White House and fellow Republicans about government regulations, the growing wealth of the most wealthy is the most dramatic economic change of recent history. Fortune magazine recently reported that one out of ten Americans own more than twice as much as all the rest of their fellow citizens combined; the 400 richest Americans alone have witnessed a tripling of their wealth in the last three decades, while the poorest have seen their meager wealth drop by almost two thirds. And these trends are growing.

The last major American populist surge in the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century had its share of demagogues, but the Populist Movement was also responding to genuine changes in American society with the wealthy adjusting economic and political rules to enable them to gain still more power. Railroad corporations provided rebates to favor certain companies, and the wealthy made large candidate campaign contributions to encourage favorable political treatment. An American citizen of the time, Mark Twain, said that history may not repeat itself, “but it does rhyme.” Are we now experiencing rhyming times with the Gilded Age? And while Levitsky is rightly worried about the Trump Administration taking steps to erode democracy by “rewriting rules to tilt the playing field against opponents,” (177) a rhyming couplet with that worry is that the president gains support at least in part because his supporters feel that the rich and powerful are rewriting rules against them.

So two cheers for Levitsky for alerting us to the dangers that our democracy faces. The intensity of polarization is alarming; the distrust on each side is none too healthy, and many leaders have been manipulating their power. However, these are symptoms of a deeper problem, in the loss of average citizens’ voices in society and in government. We can and should listen to Levisky’s warnings about erosions in the structures of democracy, but until we address why people are feeling powerless enough even to look for protections by turning to the kinds of undemocratic policies that erode democracy, it will be like mowing weeds without getting at the roots of the democratic challenge.

If all this seems like talk about stuff that ain’t your concern, consider this, dear students: in politics, business, and beyond, there are people hard at work trying to gain ground in the real estate of your minds for you to think with their interests, not yours. College is a great setting for building up your democratic power. The next time that annoying professor asks you to think for yourself, rather than just saying, Oh bother—not again…. Try this one on: Ok, I’ll do it, and I’ll save democracy. Each student thinking for her- or himself, and each step of personal empowerment means putting on some intellectual self-defense when those leaders come a-callin’ wanting you to think their way. That will keep democracy from eroding even before the guardrails are needed to protect against any unscrupulous politician.

Paul Croce teaches courses on values topics that manners experts tell you not to bring up at the dinner table, and he has written Young William James Thinking and essays for Huffington Post, the Washington Post, and his own Public Classroom; and he spends still more time wondering how young adults think—if you have clues, please contact him at [email protected].