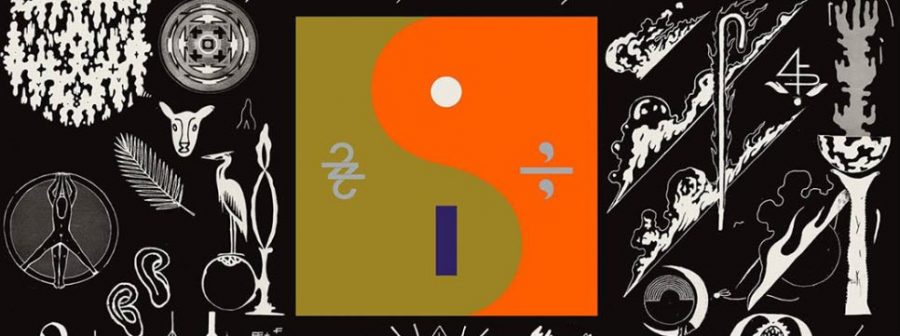

Bon Iver’s 22, A Million is worthy of its confusion

March 3, 2017

Bon Iver, an American indie folk band fronted by vocalist and songwriter Justin Vernon, became a group to watch after their 2007 hit “Skinny Love,” a single on Bon Iver’s first album of the same year, For Emma, Forever Ago. A second studio album, Bon Iver, Bon Iver, followed in 2011; both records allow Vernon’s falsetto notes to dance along soft acoustic guitar pluckings and his signature distortions and keyboard synths. After five years of impatient and eager waiting, Vernon’s fans were rewarded on Sept. 30, 2016 with Bon Iver’s newest album, 22, A Million.

22, A Million continues Vernon’s experimental distortions, but drags them onto a higher experimental plane. After an initial listen-through, I found myself disappointed. Gone were the folk-like acoustic strums and clean vocal lines I had come to love. In their place, Vernon doubled down on synths, distorted electric guitars, and voice masking with heavily edited sounds that closely resemble the experimental strains of the instruments themselves. I found myself wishing that indie folk hits like “Holocene” and “Skinny Love” could be replicated on this album instead of Bon Iver’s new experimental direction.

But as soon as I began my second listen, planning to take notes and write a scathing critical review, I found that hints of Bon Iver’s past albums’ brilliance can still be found buried like hidden treasures within 22, A Million. The album’s second song, “10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄,” contains tight drum rolls which sound like feet marching to battle, mirroring the song’s lyrical battle between love and romantic rejection. Quickly becoming a fan-favorite, “33 ‘GOD’” is the perfect jam. Beginning with flickers of synth that jump around anxiously, the song slowly crescendos with Vernon’s augmented voice meeting the drums, climaxing with the obscure lyrics, “I find God and religions, too / staying at the Ace Hotel.”

Perhaps the most experimental song is “____45_____,” which is predominantly a melody of synth horns calling to each other. However, Vernon’s voice comes in clearly and minimally edited halfway through, standing in shocking contrast to the heavily distorted instruments. His voice cuts through the horns, belting out, “I been caught in fire…without knowing what the truth is,” perhaps singing about the mysteries of heartbreak while making the listener’s heart ache in turn.

The album closes with “00000 Million,” which has Vernon’s vocals in the forefront from the get-go, singing about the failures of life. He wrestles with themes, such as the value of education, with lyrics like, “A word about Gnosis [knowledge] / it don’t buy the groceries,” and with the haunting refrain, “Well it harms me it harms me it harms. I’ll let it in.”

While by far their most experimental album to date, Bon Iver’s 22, A Million slowly burns its way into the hearts of its listeners, convincing them of its genius. My only remaining concern is over Vernon’s bizarre title choices. With songs like “715 – CRƩƩKS” and “22 (OVER S∞∞N),” fans may struggle to discuss and identify these hard-to-type names.

Vernon’s voice remains the only overarching connection across his 3 albums. But perhaps that single connection is enough; while not as easily accessible with its unique instrumentation and heavy distortion, Vernon’s familiar voice shines through each song in 22, A Million, leaving him room to explore different avenues of styles while still retaining his signature sound.