The Plastic Pandemic

The images are everywhere: fish strangled by plastic soda holders, plastic straws sticking out of turtles’ noses, and plastic mixed with seaweed. So why do people just accept it? Everyone knows the extensive damage that the use of plastic has on the environment, and it has only gotten worse with the rise of COVID-19. It feels inevitable. But does it have to be?

March 31, 2021

Humans used to reuse as much as they could. One individual produced very little trash, and people would mend and fix as much as they could to make one item last as long as possible. Unfortunately, these practices changed with the introduction of plastic.

Plastic was invented in 1907 and became widely used by the military in World War II for things like airplane windshields and parachutes, according to The Guardian. When the war ended, chemical companies turned to the general public for consumers. But they didn’t immediately see the kind of plastic waste we have today. Plastic’s unique properties made it incredibly popular: it has the potential to be used in products that last decades. But as it was used in things like construction and everyday items with increasing frequency, this is when real problems started to arise.

Unfortunately, when companies started producing plastic that was cheaper to make and more affordable, people’s main use for it became single-use items that last only for a single day. Plastic wasn’t a material that could be easily repaired at home, and slowly, people started to realize that throwing things away was “easier” than trying to fix them. As a result, throwaway consumer culture was born.

Making lower quality products so that customers have to keep coming back to buy more became an integral part of many companies’ business models, and H this practice is now known as planned obsolescence. Planned obsolescence refers to products that are designed to degrade quickly, but last just long enough so that people keep buying them, and the concept exists in multiple industries, including everything from technology to textbooks.

Electronic devices are a perfect example: they work perfectly for about two years until they suddenly begin to malfunction, and new software updates are incompatible with older models. This model proves to be problematic because many of these products contain plastic parts that end up in landfills and won’t degrade for millions of years, with the waste building up in a seemingly never-ending cycle.

In 1960, the average American generated almost three pounds of garbage per day; this number increased to approximately five pounds by 2018, according to the EPA. Additionally, the world produces approximately 448 million tons of plastic a year—a number that is expected to double by 2050, according to National Geographic. Additionally, as National Geographic points out, “Single-use plastics account for 40% of the plastic produced every year.” So, what has changed that there is so much more trash now than ever before?

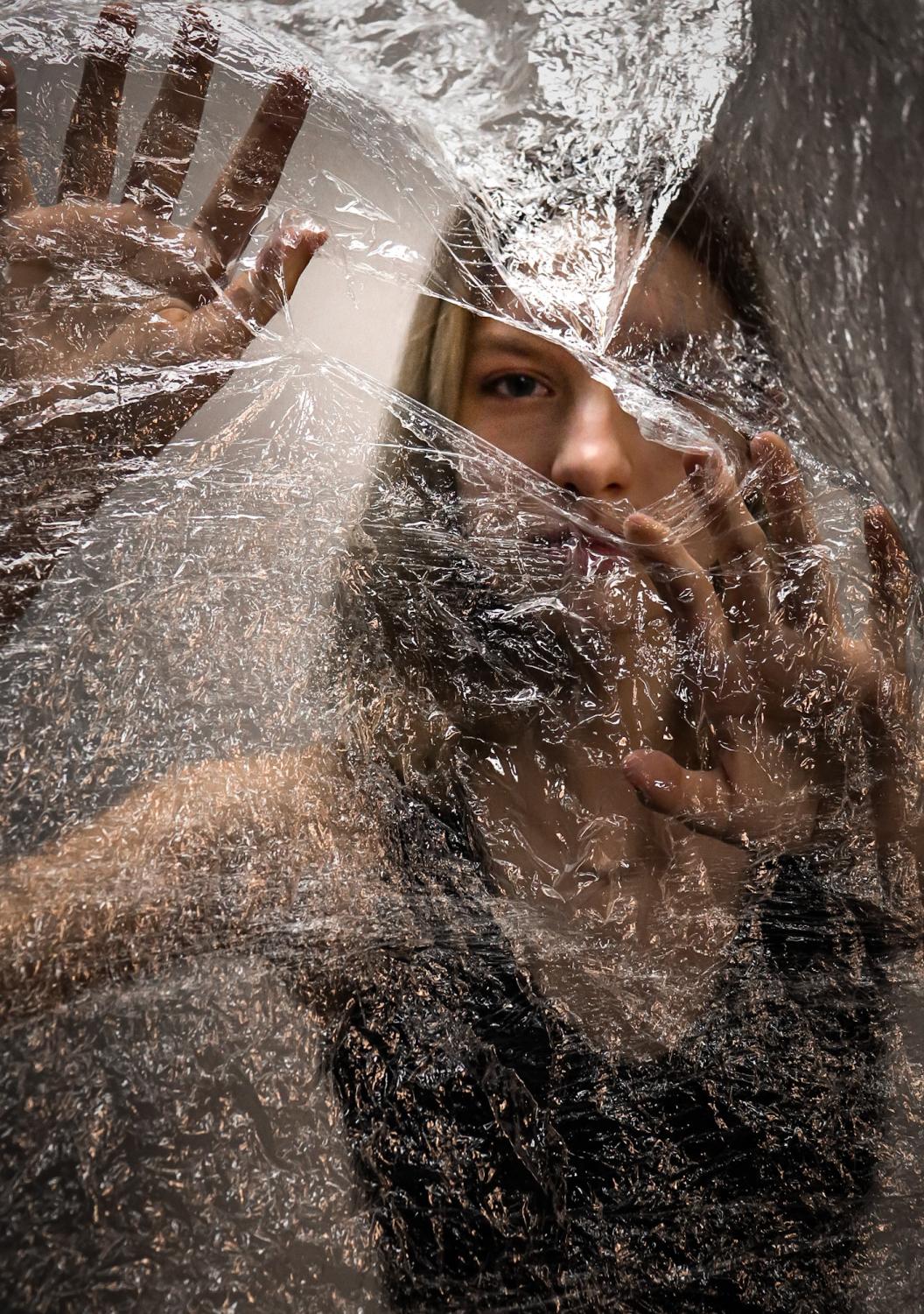

Plastic has permeated every area of human life— literally. According to Environmental Health News, “people are exposed to chemicals from plastic multiple times per day through the air, dust, water, food and use of consumer products.” For most people, it’s physically impossible to go without touching something made out of plastic every few minutes. People have failed to see how they are completely surrounded by plastic all day, every day.

It’s easy to see and react to a plastic water bottle floating in the river; one can simply pick it up and toss it in the recycling bin. However, microplastics are the hidden, unseen killer. Microplastics form when plastic breaks down from exposure to environmental factors like the sun’s radiation and oceans waves into small pieces (less than five millimeters in length). National Geographic explains the problem with microplastics: “They do not readily break down into harmless molecules. Plastics can take hundreds or thousands of years to decompose— and in the meantime, wreak havoc on the environment.” Microplastics have even been found in drinking water systems (standard water treatment facilities cannot remove all traces of microplastics) and in the marine animals that people eat.

Victoria Crawford (‘22), co-president of Stetson’s environmental club, shared her perspective on the negative impact plastic has on the environment and what can be done in the future. Crawford drew attention to the beach cleanups the environmental club hosts.

“When we do our beach cleanups, I literally could look at one piece of, let’s say, a three foot by like three foot piece of sand, and if you look hard enough, you will find microplastic critters, small broken down pieces of plastic, everywhere. Or if you put a filter through the water, you will find microplastics, and people don’t really realize how big of a problem it really is,” said Crawford. In an attempt to combat this problem, the environmental club has repurposed the microplastics they have picked up from the beach and used them in art projects.

Plastic usage has only gotten worse during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many restaurants, even Stetson’s dining hall, have resorted to single-use plastics for plates, utensils, and take-out containers in an effort to be more sanitary. Starting in March of last year, the Commons replaced the reusable ceramic plates for ones that are disposed of at the end of a meal. All the utensils and their packaging is plastic, and the cups are plastic too. This was understandable, however, given the current situation. Taking precautions to be as sanitary as possible is the right choice during a global pandemic. But we see that plastic usage isn’t just contained to the Commons either: think of all of the plastic containers that hold fruit and sandwiches and all of the plastic cups in the Hat Rack. While many of these items are recyclable or compostable, nothing is reused.

Candra Reid, Senior Director of Dining Services, provided insight as to why these changes were made in the Commons and if reducing plastic usage was a consideration. “Our main goal just went to the safety and the health of the community. So ultimately, the decision to use plastic was pretty much a no brainer for us. It wasn’t about you know, saving—I don’t want to say it wasn’t about saving the environment. But our main focus wasn’t on sustainability. Our main focus was on the health of everybody making sure that we’re doing everything that we could to limit exposure. So that was ultimately the goal as far as it’s moving to plastic, and that was what it continued to be,” said Reid, explaining the thought process behind these decisions at the beginning of the pandemic.

Only recently following the move from tier 1 to tier 2, did the Commons return to using washable plates.

As for how these changes would be implemented in tier 2, “In our plan…there was always the chance of us being able to do a hybrid, of being able to utilize some of our plates and things that we have on campus, as well as continuing the use of disposables in whatever capacity was needed. So ultimately, whenever we moved into tier 2 for the university as a whole, that was whenever we were able to decide, okay, we can now limit our usage; because of course, we know sustainability is a huge factor for the Stetson community. Basically, that was the idea behind it,” said Reid.

Essentially, the decision came down to safety. “Once we felt that the university was in a good place and felt that it was safe enough for us to go into tier 2, we made that decision to utilize our plates. Of course, we’re still using the cups and utensils, because those are the things that for the most part come in contact with each person on a consistent basis. So we still thought it was still necessary that we use the disposables for those things, but we were able to slowly incorporate back in our plates.”

Reid also made sure to bring up the compostable items that are used in the Hat Rack and the Coffee Shop: “We’re using compostable straws in the Hat Rack, as well as the Coffee Shop. The container that the food is actually held in at BYOB— the burrito bowl— and the cups that are actually being utilized in the Hat Rack, in the Coffee Shop are completely compostable. We’ve made sure to incorporate those pieces throughout campus, keeping up with our sustainability initiatives.”

The effort to be more sustainable on campus is still ongoing though. “There are some places or some pieces that we haven’t been able to do as much as we would like to. I know it’s been mentioned about the plastic from Jack & Olive. But whenever we outsource into a company, a lot of times we have to utilize the product that they’re actually giving us, and that’s the product they provide: so like the sandwiches in the plastic container, things like that. We’ve mentioned to them that it’s something we want to happen, but it hasn’t happened yet. But that’s one of the downsides to us outsourcing and getting things in from other places,” Reid explained.

Reid also mentioned some ways Dining Services reduces waste in the Commons: “We do have our food pulper that is in use. So we utilize that in the Commons; we put our food products in it so that it goes through the process, and it breaks down our [plastic] bag usage from, like, 12 to one. So we’re not sending as much trash to the land fields that we used to without having our food pulper—that’s one thing that we’ve done. The plates that we do utilize in the Commons are actually made out of bamboo. So that’s another piece of the sustainability that we like to bring and try to make sure that we’re doing the best that we can to bring those different efforts into play.”

Crawford also shared her perspective as a student, copresident of the environmental club, and member of the Environmental Working Group on what she called “a plastic issue even on campus.”

“If you go to the coffee shop, it’s all single-use plastics. We arranged a meeting with Dining Services to try to fix that issue. And it’s very, very difficult. We tried, but we were not very successful because the Coffee Shop is run by a company called Jack & Olive who supplies all the food and everything, and it’s already prepackaged. It’s a decent sized company. So we held an event where we all petitioned and wrote emails to the company asking if they could reduce their single-use plastic usage. A lot of their stuff is wrapped in plastic that doesn’t even need to be wrapped in plastic, plastic and then more plastic and more plastic around it. But we didn’t hear back. So it’s hard with the big companies, and Stetson has a contract with them,” she said.

Crawford also offered insight on how Stetson could reduce its plastic use in areas other than dining: “I’ve also considered maybe the bookstore could easily just do reusable bags that said ‘Stetson University’ and it could be like a promotional item for them as well. People would advertise the university when they go shopping or whatever instead of using plastic bags when they give you whatever you get there. And that’s such a simple switch.”

More information on sustainability efforts on campus by students was provided by Josh Finkelstein (‘22), president of Stetson’s Student Government Association: “SGA recognizes the importance of sustainability on campus and the effect our actions have on our environment. In the past, SGA partnered with the Environmental Fellows to establish a Revolving Green Fund which provides funding for environmentally friendly projects positively impacting campus. Currently, SGA is in talks with the Environmental Fellows to establish a Revolving Green Fund Committee to establish cross organizational dialogue to streamline solving and improving sustainability projects,” said Finkelstein.

Reid, Crawford, and Finkelstein’s responses show that sustainability has been a topic of discussion at Stetson University and that there are people who are pushing for more to be done. Even though more can in fact be done on campus to reduce the amount of plastic waste, this does not dismiss how the use of ceramic plates and composable items does certainly help. But Stetson University is only a microcosm of the entire world, and the world needs real solutions to the mounting problem of plastic waste.

One would think the solution to plastic usage would be just to recycle it, right? That’s exactly what large companies that produce plastic want people to think. On the contrary, not as much of our waste is recycled as we might expect.

The nation’s largest oil and gas companies that produce plastic knew for years that the majority of it would never be recycled, “Yet the industry spent millions telling people to recycle, because, as one former top industry insider told NPR, selling recycling sold plastic, even if it wasn’t true,” according to NPR. They believed that consumers would be less concerned about the negative environmental impacts of plastic if they thought it would all be recycled.

Starting in the 1990s, TV ads emphasizing how “great” plastic was because it could be recycled were pushed more and more. The encouragement to recycle appeared to come from environmentalists, but in reality, according to NPR, “the ads were paid for by the plastics industry, made up of companies like Exxon, Chevron, Dow, DuPont and their lobbying and trade organizations in Washington.” Ads like this ran for years, despite the people who created them knowing that recycling plastic was costly and that it would likely never happen on a large scale. By promoting the recycling trend, large companies that produced more waste than anyone else successfully validated the production of single-use plastics.

Recycling is a lot more complicated than most of us think. Most people are happy to roll their recycling bin to the curb once a week and then forget about it. In actuality, “Single stream recycling, where all recyclables are placed into the same bin, has made recycling easier for consumers, but results in about one-quarter of the material being contaminated,” The Earth Institute at Columbia University explains.

Most people do recycle with the right intention. The problem is that so much needs to go right for something to be recycled, and absolutely nothing can go wrong. For example, if a container has any remaining remnants of food, it’s contaminated, and contamination can prevent large batches of material from being recycled—not just the one item.

According to the EPA, of the 292.3 million tons of municipal solid waste generated by Americans in 2017, only 69 million tons were recycled, and only 8% of plastics were recycled.

Another problem is that many items that people assume can be recycled, actually can’t be: plastic straws can’t, plastic bags need to be dropped off at certain locations, and eating utensils can only be recycled in some cities. To make matters worse, there are also multiple types of plastic, and only some of them can be recycled. So, as we can see, the process of recycling is so complex that it is affected by a myriad of factors.

There’s a political element to the recycling problem as well. The United States has never actually recycled within its borders, contrary to what most would probably think. Recycling facilities collect and transport everything, but they have someone else do the actual recycling.

China has long been the United States’ go-to country to do our recycling. For years, the United States exported millions of tons of plastic for China to recycle. What actually happened is that 30% of these exports ended up contaminated by non-recyclable material, and a lot of it ended up polluting China’s oceans during transport, as reported by The Earth Institute at Columbia University.

As a result, in 2018 China banned the import of any plastics that were not up to their new, higher standards. The United States was forced to turn elsewhere: Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand. But these countries then also instituted bans on imported plastic waste because of the contaminated water and crop death it caused. The United States still ships plastic waste abroad to various African countries whose environmental standards are lower in comparison and offer a cheaper source of labor, but the dwindling number of countries who are willing to take U.S. waste is making the recycling industry less lucrative.

The lack of a market for used plastics has caused problems all over the United States in cities that used to sell recyclables but now have to pay to get rid of them. Municipalities have even had to charge residents more to recycle or end recycling programs all-together.

Aside from the physical waste that litters every area of the Earth, plastic production has other unintended consequences. The creation of plastic requires oil, gas, and coal, and Yale University states that “12.5 to 13.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent are emitted per year while extracting and transporting natural gas to create feedstocks for plastics in the United States.” Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that traps heat, raising the Earth’s average temperature and causing climate change. Even more carbon dioxide is emitted during the refining process.

The World Energy Council reported that “if plastics production and incineration increase as expected, greenhouse gas emissions will increase to 49 million metric tons by 2030 and 91 million metric tons by 2050.” Every part of the life cycle of plastic, from its development to its incineration, has a negative impact on the environment. Increasing carbon dioxide emissions is the opposite direction of what is needed in the effort to mitigate climate change.

There are so many alternatives to plastic, but one possible solution to its overuse is just to use it in a different way. Plastic can be a long-lasting material, so treating it as a reusable material would reduce waste. People already do this with reusable water bottles, and it can be done with other things too.

The New York Times lists alternatives to plastic, including fiber-based containers for food, seaweed extract for single-serving condiment packets, and mushroom tissue for packaging foam. All of these options have the potential to replace plastic or reduce its use, but most people are likely to use whatever is cheapest and easiest, and that remains to be single-use plastics. Unfortunately, widespread use of alternatives is unlikely without government intervention.

Some local and state governments have recognized the risk plastic use poses to the environment: eight states have banned plastic bags, and many individual cities have instituted their own bans according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. But this is still a small portion of the United States, and these bans have only come voluntarily. Despite efforts at the local level, comprehensive federal legislation does not exist yet in the United States. The Regulatory Review points out that, “Voluntary steps to address plastic pollution can be positive but are not enforceable. Only regulation can create a level playing field that applies the same standards to all businesses.”

This effort has become more complex with the pandemic. The European Union banned some single-use plastics, but the United Kingdom delayed its ban on plastic straws; California and Massachusetts had banned single-use plastic bags, but according to The Nicholas Institute at Duke University, this was suspended. Understandably, countries are prioritizing efforts to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 to keep their citizens healthy, but this comes at an unfortunate cost.

Not only are regulations being rolled back, but plastic usage is increasing in more areas than just dining. Personal protection equipment, or “PPE,” is something that it seemed like everywhere had a shortage of at the beginning of the pandemic. The single-use masks and gowns are largely made from nonrecyclable plastic and are not worn for more than a few hours. Because they can’t be recycled, this further adds to the plastic waste that has already surged.

A holistic approach to plastic pollution at the national level could be to employ a number of strategies to tackle the issue, including source control to reduce consumer use of single-use plastic items, improvement of recycling and waste management infrastructure, and research and development. It would also provide a national framework to reduce single-use plastic waste.

Europe is currently ahead of the United States in creating legislation to reduce plastic use. This past year, the European Union announced an agreement to ban single-use plastics most often found on beaches, like plates, utensils, and straws, while reducing single-use items like food containers, cups, and bottles, according to The Regulatory Review. The plan will include efforts to raise awareness and provide incentives to manufacturers to develop lower-polluting versions of their products. The European Union expects that the new policy will help prevent future costs in environmental damage.

The continuous encroachment of plastic into every area of life on Earth is a problem that will likely take humans decades to solve. But choosing not to try to solve it isn’t an answer. The Regulatory Review reports that over 700 species have been impacted by plastic debris in the ocean. Plastic waste is everywhere, and plastic’s indestructible qualities as a material are exactly the reason why it has the potential to do so much damage.

Much of the responsibility falls on those who produce plastic, and those who have the power to regulate those who produce it. But taking individual actions like avoiding single-use plastics and using alternative materials to reduce waste is still a step that matters. By doing so, it encourages others to do the same. As students, we can even advocate for a more sustainable future at Stetson and implement sustainable practices into our own lives.

Victoria Crawford suggested ways that individuals can easily reduce the amount of plastic they use on a daily basis: “I’ve noticed a lot of people don’t recycle in their personal apartments. So I think recycling could definitely be more incorporated into people’s daily lives. But recycling should be a last resort—it should be reduce, reuse, recycle. So for people that like little switches, obviously, I’d say start with a reusable water bottle. That’s always like an easy thing. There are tons of zero waste alternatives: bags at the grocery store —they also sell these bags for your produce so you’re not using plastic— and bamboo toothbrushes. Instead of buying makeup wipes, you can use reusable cotton round pads that you just put in the wash. There’s so many little switches that you can make that actually have a huge impact.”

When asked why so many people seem to accept plastic pollution instead of taking action, Crawford said, “It’s like the Tragedy of the Commons. Where it’s like, oh, I don’t have to do this, because it’s not my personal beach. But it’s our Earth. It’s everyone’s personal responsibility to take care of it.”