big red

March 15, 2019

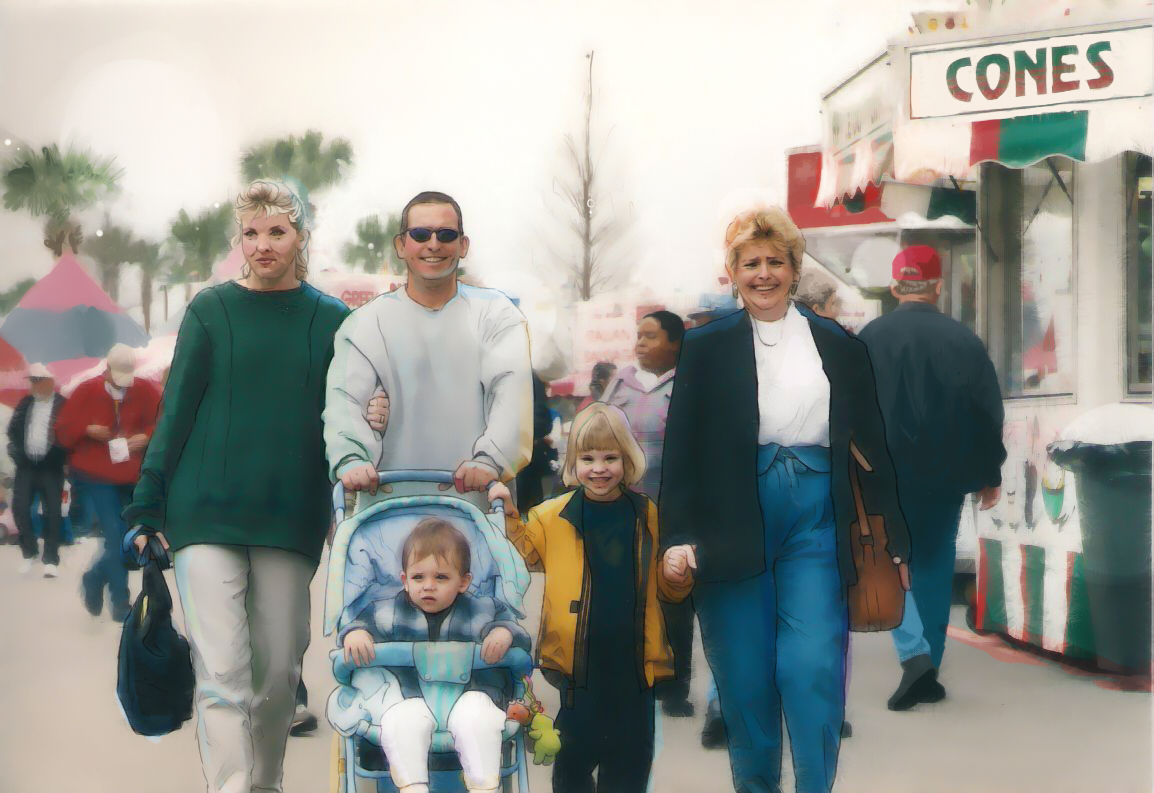

When Hurricane Charley destroyed my home in 2004, I lived in a rental house with a leaky roof for almost a year. My brother, mother, and I had nine cats, and two bedrooms to squeeze them all into. My father, Poppy, made the decision to stay in the skeleton of the home we had left behind, thirty minutes away, sleeping in sodden, molding fiberglass each night. I was seven, my brother four, and all we knew to ask our mother was why. Sometimes I wish she had told us, but to keep us safe she insisted she did not know.

Poppy was addicted to OxyContin. He was an alcoholic and a heavy smoker, and his new addiction began in 2003 when his dentist prescribed the opioid to him after a surgical extraction. Already taken by other addictions, he succumbed easily to the opioid crisis of the early 2000s.

Crisis might not be the right word. Maybe the media coverage of the past two decades of healthcare and prescription pain medication is a little sensational. However, beginning in 2001, there was a marked increase in opioid overdoses, linked by many scholars and medical professionals to the practice of overprescribing in conjunction with social and economic upheaval. The effectiveness of opioids far overshadowed the dangerous side effects and potentially addictive properties, and by the early 2000s, chronic pain became a multi-billion dollar industry.

In 2003, the United States General Accounting Office reported that from 1997 to 2002, OxyContin prescriptions for pain unrelated to cancer grew from 670,000 to over six million. Drug-related mortality rates overall doubled between 1999 and 2013. Chronic pain linked with mental fatigue and increased overall tension to double opioid-related overdoses. This only continued to worsen in the following years.

In 2006, I believe Poppy was at his worst. My Nana, his mother, flew down from New York to visit us. We packed into my mother’s 2000 Toyota RAV4 to visit a favorite of hers, Olive Garden. Right after we ordered, he stood, saying he needed some air, and stumbled out of the restaurant. We waited. Thirty minutes later, my mother solemnly had our food packed into boxes and we left. He was nowhere to be found. We wandered the parking lot as the sun set, calling for him until it was dark.

On our way home, six miles down the road, we found him wandering alongside the highway in a daze. He was barely coherent and didn’t seem to know how he had gotten there. His mother said nothing. My mother cried. He smelled like cheap beer, garlic, and cinnamon gum. He sat between my brother and me and we went home.

Over time, these incidents became more numerous and more frequent, and more often than not Poppy was not home. Instead, he was crashing on other people’s couches, buying OxyContin from them when his prescription was no longer enough, and selling marijuana out of his truck to support his habit. He began spreading rumors about my mother and accusing her of cheating on him and he became increasingly delusional and aggressive as time went on.

OxyContin was initially marketed as combating the addictive properties of opioids as a delayed-release product, the first on the market of its kind. Unfortunately, though, this was untrue. Instead, the new drug wore off earlier than research had initially seemed to conclude, leaving people experiencing symptoms of withdrawal and scrambling to take more. It came out later that this was known by Purdue, the corporation behind OxyContin, and was ignored. Instead, higher doses were prescribed. According to an investigation conducted by the LA Times in 2016, over “half of long-term OxyContin users are on doses that public health officials consider dangerously high.”

I remember hiding under tables to watch my parents fight. I learned who not to be from listening to them scream. I watched prescription painkillers and Bud Light take Poppy away. I watched him stick his rotting teeth back in with cinnamon gum. I watched him fading in and out of consciousness over tubs of vanilla ice cream while coming down from a high. I watched him package pills in travel containers to sell, and then partake of his own supply.

As a child, I found this unsettling and often annoying, but not entirely unexpected from a father who was already incredibly distanced from his children’s lives. It was also far beyond my scope of understanding. I was eight, nine, ten years old and had so little concept of what addiction even meant. I think my mother had the best of intentions in keeping it from me, but often I wish she had just told me the truth.

My understanding of addiction came later, first from my mother, who believes even now that it is spiritual weakness, that addicts choose and are complicit in their own failure. Studies on drug addiction point us in a different direction. OxyContin is ruthless and incredibly fast, creating dependence in as little as one dose. Journalist Beth Macy, in her bestseller Dopesick, goes into this a little further, fleshing out the misconceptions that surround drug abuse into a more universal issue, one that everyone is vulnerable to despite their income level, age, race, or background.

The chemical makeup of OxyContin is similar to that of heroin, and for many, a prescription of OxyContin leads directly to a later addiction to more serious drugs. Because of the effects of withdrawal, those taking prescription doses of OxyContin often move on to taking doses early, to snorting pills to quicken the effects, to requesting ever larger doses, and then to finding similar ways to attain the feeling of the narcotic high.

My parents’ divorce was finalized in early 2009 when I was 12 years old. This is the classic American story nowadays, but unlike most, my parents maintained a relationship long after the ink dried on their divorce papers. We were at the height of the housing crisis in my small town, and my father was homeless, so even after moving into a much smaller home, my mother let him take up new residence in our living room.

He was a disaster. Shocked that she had carried her life on without him, he rekindled their relationship while dating another woman behind her back. She gained weight after she quit smoking during a bout of pneumonia, and I listened to him tell our neighbor about what a “fat slob” she had become. God stopped talking to me. I stopped talking to anyone. His dentist fled the country, charged with multiple counts of drug trafficking and over-prescription.

The last time I spoke to my father, he had recently tried for custody. I visited his home and found myself surrounded. It smelled like Bud Light and an Italian kitchen. It smelled like Big Red. There were empty pill bottles under the couch. It was 2015, and I was almost 18, but for a moment I felt nine years old all over again, and I couldn’t help but wonder how things might have been had he listened to my mother, to his own mother, and to the needs of his kids. Addiction is a disease, and many are unable to tear themselves away from opiate addiction, but even still, many do.

I am not angry at my father. More than anything, I want to ask him exactly what I asked my mother in 2004—why? One hundred thirty people die each day as a result of opiate overdoses. I wonder if he thinks as often as I do about when he, too, will die.