More Than Papers: How Stetson is Affected by DACA

October 6, 2017

Veronica Faison is the Managing Editor. Additional reporting by Naomi Thomas, Senior Staff Writer. Photographs and illustration by Kitty Geoghan.

The following interview is with a Stetson student DACA recipient. His name has been redacted and changed in order to ensure anonymity and safety.

First-year political science and English double major John Smith aspires to be a member of Congress. “I feel like it’s the best way I can help people,” he said. “Being an American is important. I care about this country very deeply and I see a lot of problems I want to be able to help with.” However, current policy impedes that dream. The United States does not recognize him as a citizen. He is a recipient of DACA, also politically referred to as a “Dreamer.”

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, known as DACA, allows undocumented individuals who met several requirements to stay in the country for two years without being persecuted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). To qualify, applicants must be under 31 years old and have arrived to the United States before turning 16 years old, have no law infractions and actively pursue education. Before the two years have elapsed, the DACA recipient must reapply to receive another two years.

Brought to the United States as 7-years-old, Smith’s mother and grandmother sought to escape violence plaguing their central-American country. “It wasn’t for economic gain,” said Smith. “My mother had a good job as an accountant. We came here for our safety.” The poverty and corruption of the country spurred gang activity which often targeted young children by force, Smith described. “My mother always thought of putting me first in all the decisions that she made. If we had stayed I would have likely been forced to join and enter a life of violence,” he said. “There was nothing there for me.”

Despite finding safety and refuge in the US, Smith’s single-parent household has faced struggle. Sharing a one-bedroom apartment between Smith, his mother and maternal grandmother, Smith recognized the necessity of helping his family early on.

When Smith was 14-years-old, the Obama administration introduced the DACA in 2012 as an executive order (after the DREAM Act failed in 2010). Smith recalled being skeptical. “If I applied for this I would have to give up my home address, where my family lives as well, and I would be coming out of the shadows.” The policy was also not signed into law by Congress. “It wasn’t for the long run,” said Smith. “As we’ve seen now, it’s a short-term policy that any president could take away.”

However, for Smith, the benefits outweighed the costs. Under DACA, Smith would receive a work permit, driver’s license and social security number. This would allow him to contribute household income, drive his mother to work without fear of being stopped by police, and, eventually, apply to college. DACA is, however, not a path to citizenship. The application also costs approximately $485 each renewal (which had to be filed before the two-year difference period elapsed).

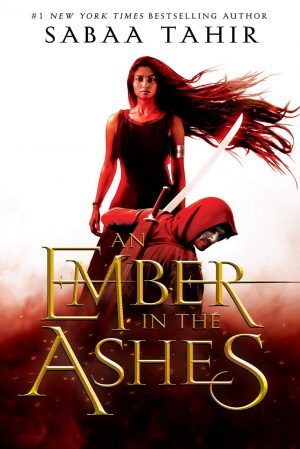

Though having a social security number allowed Smith to apply to college, DACA status did not allow him to receive any federal grants. Undocumented people are not able to access any federal aid despite still paying taxes, contrary to popular stereotype. Smith relied on only institutionally funded aid to afford college—which private schools, such as Stetson, offers. With his academic record and dedication to community service, Smith attained a scholarship that allowed him attend. Referencing the “American Dream” symbolism in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Smith said, “Getting into college and being able to afford it was my green light across the bay.”

However, DACA was recently given a red light. The Obama administration was almost sued over the constitutionality of the program in 2015, and, on September 5, 2017, President Trump announced his decision to repeal the program entirely; this reversal will affect the lives of nearly 800,000 individuals. The president gave Congress six-months to introduce and pass legislation to help current DACA recipients. Though many fear that Congress will not be able to reach an agreement in time, Smith believes that Congress will come up with a bill, and advocates that Dreamers should also have a path toward citizenship. “Congress is made up by people and people see reason,” said Smith. “[Dreamers] have abided by the law and overcome so many challenges that society has placed upon us. We want to be part of this nation.”

When asked why he wanted to share his story, Smith hopes that his story can appeal to those who are currently against immigration. By humanizing the immigrant narrative, he hopes to particularly appeal to Stetson donors that may not support DACA students because, ultimately, donations help fund the institutional aid that DACA students rely on.

“Growing up in the US it was difficult to talk to anyone, teachers, even friends, about my status,” said Smith. “I was afraid that being this vulnerable would have repercussions, but I thought maybe some good would come out of it.”

While the Department of Homeland Security is no longer accepting new DACA applications, current recipients whose deferrals expire before or on March 5, 2018 had until October 5, 2017 to reapply.